Origin

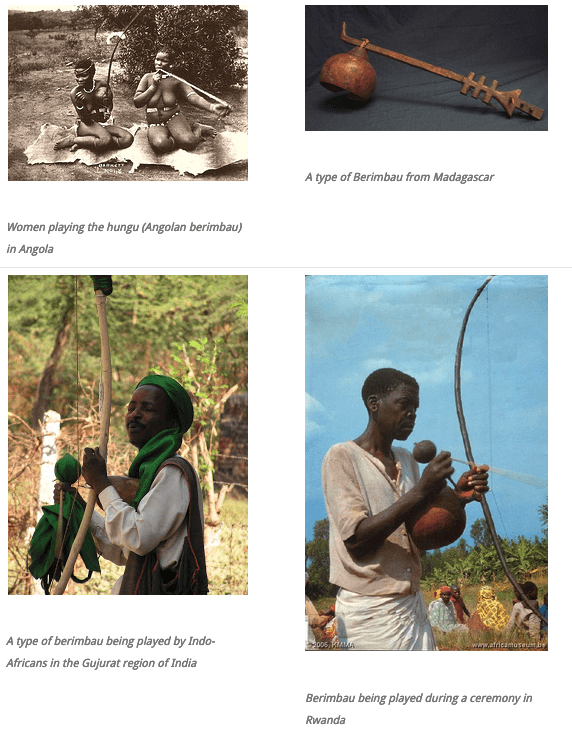

There is little doubt that the berimbau is African in origin. There are several similar instruments found all across africa as well as parts of India. Despite this the berimbau as it exists in Brazil is believed to be African in origin because:

In fact in Angola the berimbau is called hungu or m’bolumbumba. It is an instrument used a lot by nomads and can be seen as far south as Swaziland and all the way to the east coast of Africa to Madagascar and the island of Reunion. This is interesting because based on 19th century paintings of capoeira, some historians believe the berimbau was incorporated with capoeira by lone singers playing the instrument. In some case a roda was formed around the lone singers by practitioners of capoeira or the reverse was the case when a berimbau player stumbled upon a roda. The lone African singer would sing songs of love, slavery and of Africa. He or she would sing songs about society, religion, and what was going on at the time. People would gather round and begin to respond to the words in the form of a chorus. “E vai você, e via você”, and the people responded “Dona Maria, como vai você?”

Lone singer playing berimbau. 1826 painting by Jean Baptiste Debret

The custom of a lone singer nomad is a very popular one throughout africa. In Senegal and Mali they are called griots. Furthermore, the Malês which was a major ethnic group brought as slaves are found in these countries.

Bariba warrior showing off the hunting bow that most likely evolved into the berimbau

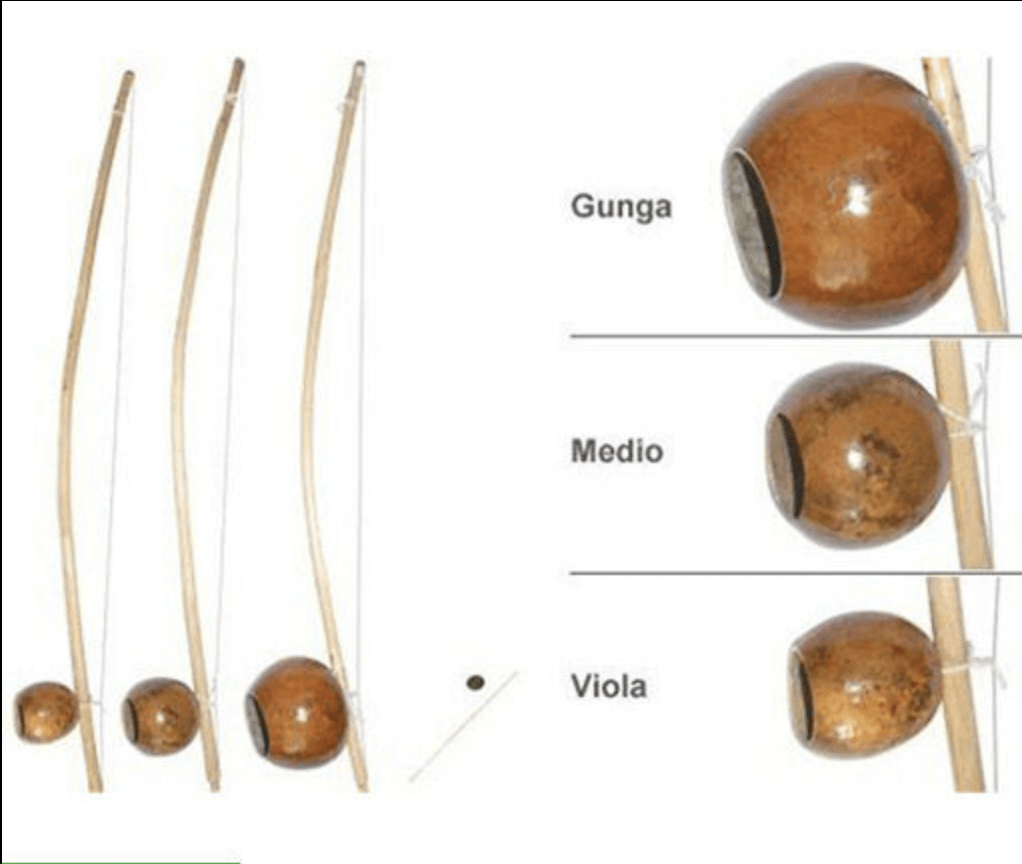

The prevailing theory is that the berimbau was probably initially just a bow used for hunting or war. But at some point a resonator was attached to it to transform this bow into a musical instrument. Today the instrument is most commonly identified as the symbol of capoeira. The berimbau has many names in Brazil: berimbau gunga, berimbau viola, berimbau de barriga, orucungo, gobo, bucu,bumba, and macungo.

O berimbau e quem comando jogo, meaning it’s the berimbau that dictates the game. The berimbau can produce distinctive rhythmic patterns called toques. The different toques signal the style of the game (Learn more about the different torques of the berimbau). For example:

Listening to the toque do berimbau is important for developing a good rhythm in a player’s game. A capoeirista’s game becomes more fluid when he or she is in sync with the berimbau and the rest of the instruments. The sound of the berimbau should put the player in an almost trance-like state where all the movements begin to flow naturally in time and with heightened awareness.

The person playing the Berimbau is usually also the singer and leader of the roda. He or she sings and plays the berimbau accompanied by the other instruments. The other instruments must follow the Berimbau’s lead as it changes the pace and style of the game: In other words, the berimbau player is the cantador and should be the root of the roda.

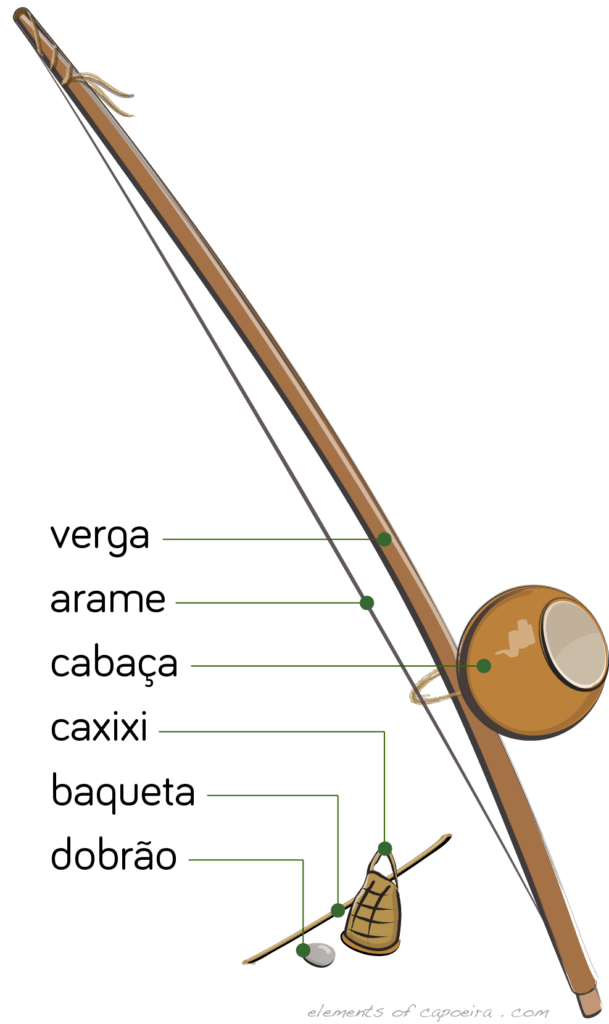

Anatomy of the Berimbau

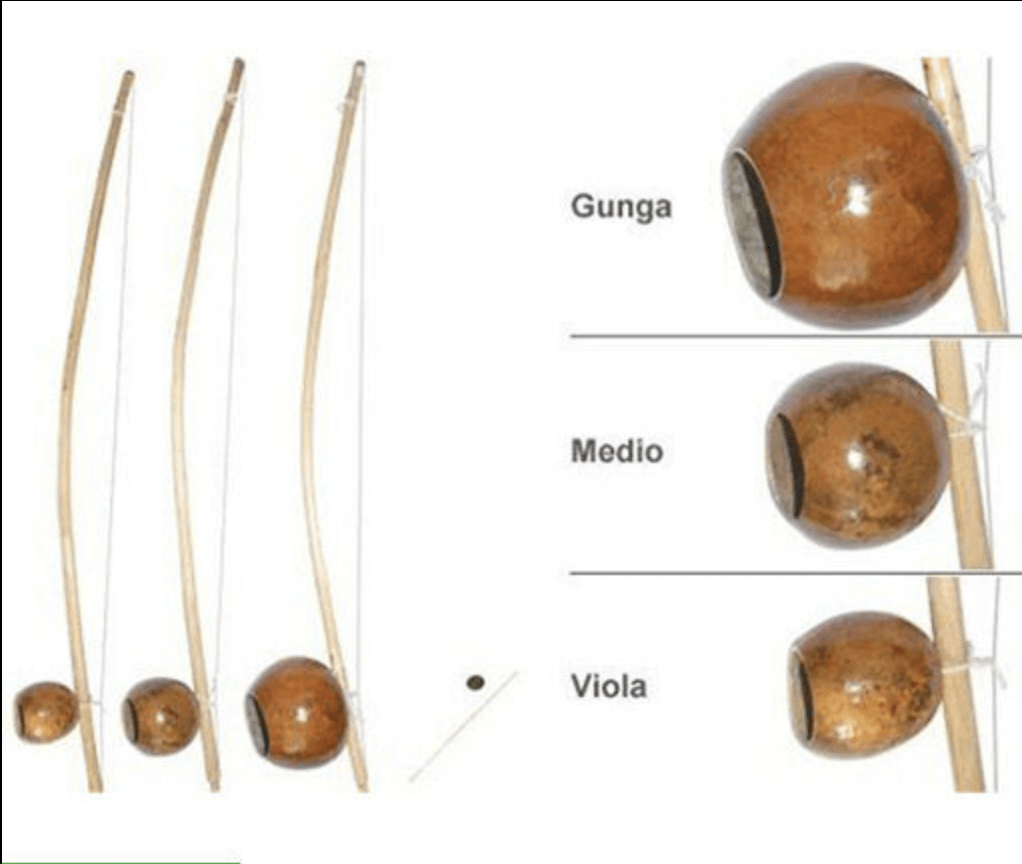

Types of Berimbaus

In fact in Angola the berimbau is called hungu or m’bolumbumba. It is an instrument used a lot by nomads and can be seen as far south as Swaziland and all the way to the east coast of Africa to Madagascar and the island of Reunion. This is interesting because based on 19th century paintings of capoeira, some historians believe the berimbau was incorporated with capoeira by lone singers playing the instrument. In some case a roda was formed around the lone singers by practitioners of capoeira or the reverse was the case when a berimbau player stumbled upon a roda. The lone African singer would sing songs of love, slavery and of Africa. He or she would sing songs about society, religion, and what was going on at the time. People would gather round and begin to respond to the words in the form of a chorus. “E vai você, e via você”, and the people responded “Dona Maria, como vai você?”

Lone singer playing berimbau. 1826 painting by Jean Baptiste Debret

The custom of a lone singer nomad is a very popular one throughout africa. In Senegal and Mali they are called griots. Furthermore, the Malês which was a major ethnic group brought as slaves are found in these countries.

Bariba warrior showing off the hunting bow that most likely evolved into the berimbau

The prevailing theory is that the berimbau was probably initially just a bow used for hunting or war. But at some point a resonator was attached to it to transform this bow into a musical instrument. Today the instrument is most commonly identified as the symbol of capoeira. The berimbau has many names in Brazil: berimbau gunga, berimbau viola, berimbau de barriga, orucungo, gobo, bucu,bumba, and macungo.

O berimbau e quem comando jogo, meaning it’s the berimbau that dictates the game. The berimbau can produce distinctive rhythmic patterns called toques. The different toques signal the style of the game (Learn more about the different torques of the berimbau). For example:

Listening to the toque do berimbau is important for developing a good rhythm in a player’s game. A capoeirista’s game becomes more fluid when he or she is in sync with the berimbau and the rest of the instruments. The sound of the berimbau should put the player in an almost trance-like state where all the movements begin to flow naturally in time and with heightened awareness.

The person playing the Berimbau is usually also the singer and leader of the roda. He or she sings and plays the berimbau accompanied by the other instruments. The other instruments must follow the Berimbau’s lead as it changes the pace and style of the game: In other words, the berimbau player is the cantador and should be the root of the roda.

Anatomy of the Berimbau

Types of Berimbaus

How to Play

Here’s a video of Mestre Caxias of Grupo Capoeira Brasil teaching how to play Berimbau:

There are three key sounds produced by the berimbau

Where to Get a Berimbau

The best place to get a berimbau is from your mestre or school who has played berimbaus for years and knows the science of making one. If you don’t live near a mestre like that then the next best thing it to attend a workshop or go for capoeira events such as a batizado. Most of these events will have a variety of capoeiristas and usually a few mestres selling their berimbaus. They have a variety of high quality berimbaus and also other instruments and accessories.

You can also make a berimbau yourself with the guidance of someone skilled in the art. There are lots of resources online to help guide you.

References

ALMEIDA, Bira. Capoeira: A Brazilian Art Form, ISBN: 9780938190295

CAPOEIRA, Nestor. The Little Capoeira Book, ISBN: 9781556434402; Capoeira: Roots of the Dance-Fight-Game, ISBN: 9781556434044